A window into the cultural history of Pre-Islamic Afghanistan

This imposing Buddhist sanctuary rises on a hill which dominates a vast portion of the Dasht-i Manara plain. The excavation of the site, carried out by the Italian Archaeological Mission between the late 1960s and the late 1970s, was resumed in 2003 under the direction of Giovanni Verardi and again stopped because of the unsafe security condition in the area.

As attested by an inscribed votive pot found in the site, the sanctuary was known in the past as the Kanika mahārāja vihāra (“the temple of the Great King Kanishka”). This evidence confirms that the sacred area of Tapa Sardar was founded during the Kushan period (either by Kanishka I or Kanishka II, in the 2nd or 3rd century CE) and also reinforces the hypothesis that it may well correspond to the Šāh Bahār (“The temple of the King”) that, according to the Kitāb al-buldān, was destroyed in 795 CE by the Muslim army.

After being destroyed by a fire (possibly to be related to the first Muslim incursion in 671/672), Tapa Sardar underwent an extensive reconstruction in the late 7th/ early 8th century CE. The date of the final abandonment, though uncertain, does not precede in any case the late 8th/9th century CE. As clearly highlighted by the archaeological investigation of the site, Tapa Sardar was a prestigious religious centre where not only new artistic forms were experienced and established but also periodical ceremonies of great political relevance might have taken place. This is suggested by iconographies depicting members of the ruling élites and, especially in the last phases of the site, cultic images symbolically connected to the theme of the protection of the “Buddhist kingdom”.

2002 The checking of the old inventoried materials

2002 The checking of the old inventoried materials 2003 A view of the Upper Terrace

2003 A view of the Upper Terrace 2003 Cleaning of the site

2003 Cleaning of the site 2003 Geo-referentiation of the site

2003 Geo-referentiation of the site 2003 Resumption of work

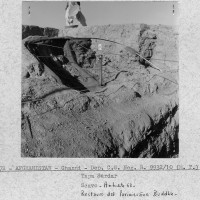

2003 Resumption of work 1962, excavation work on the Upper Terrace (R1786_6)

1962, excavation work on the Upper Terrace (R1786_6) 1962, the first soundings at Tapa Sardar

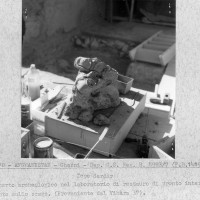

1962, the first soundings at Tapa Sardar Fragments of the inscribed pot mentioning the 'Vihara of the Great King Kanishka'

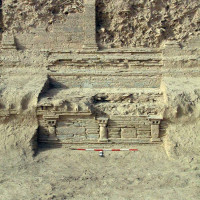

Fragments of the inscribed pot mentioning the 'Vihara of the Great King Kanishka' 2003 Great Stupa, detail of the architectural elements

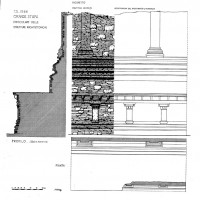

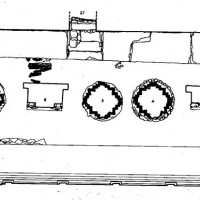

2003 Great Stupa, detail of the architectural elements Great Stupa, section and axonometry showing the details of the architectural elements (Dep. CS 4005)

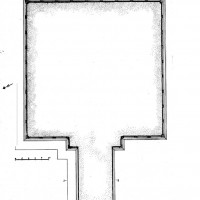

Great Stupa, section and axonometry showing the details of the architectural elements (Dep. CS 4005) Plan of the Great Stupa (Dep. CS 70-E3)

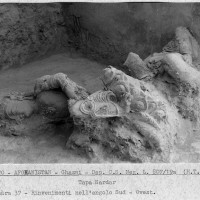

Plan of the Great Stupa (Dep. CS 70-E3) 2003 The Great Stupa, south-east corner

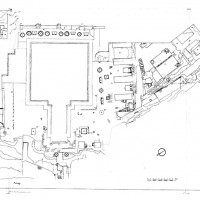

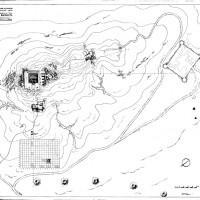

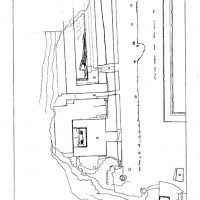

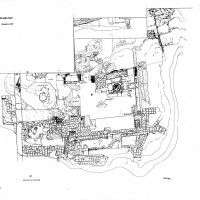

2003 The Great Stupa, south-east corner General ground plan of the site (Dep. CS 4010-f)

General ground plan of the site (Dep. CS 4010-f) The topographic plan of the site (Dep. CS 4046)

The topographic plan of the site (Dep. CS 4046) 2003 The tepe seen from the plain

2003 The tepe seen from the plain 2003 The tepe seen from the plain

2003 The tepe seen from the plain

The general features of the site

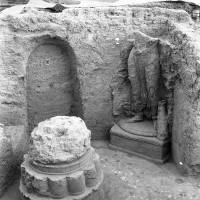

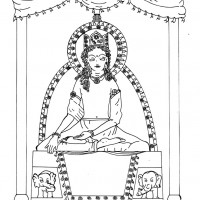

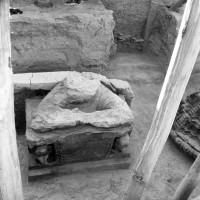

In the Upper Terrace, the Great Stupa was surrounded by richly decorated chapels and by small star-shaped stūpas and statues representing enthroned figures of Buddhas and/or Bodhisattvas. Minor sacred areas (and most likely the monastery) were located on lower terraces.

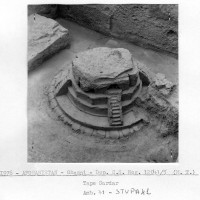

Minor cultic areas - Room 87, with star-shaped fire altar (neg 11461-3)

Minor cultic areas - Room 87, with star-shaped fire altar (neg 11461-3) Upper Terrace, row of stupas during excavation (MNAOR 3411 CS 1799-6)

Upper Terrace, row of stupas during excavation (MNAOR 3411 CS 1799-6) Chapel 23 after excavation (neg. CS 8148-4 MT)

Chapel 23 after excavation (neg. CS 8148-4 MT) Chapel 23, detail (neg 8159-15)

Chapel 23, detail (neg 8159-15) Chapel 23, detail (neg 8148-7)

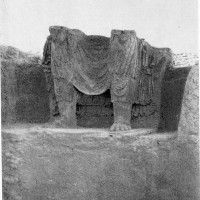

Chapel 23, detail (neg 8148-7) Chapel 17, main cultic image (Buddha Maitreya) (neg 6747-4)

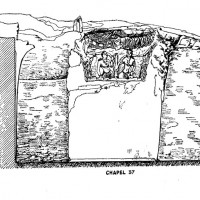

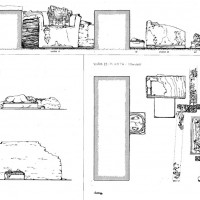

Chapel 17, main cultic image (Buddha Maitreya) (neg 6747-4) Chapel 37, elevation (drawing by N. Labianca)

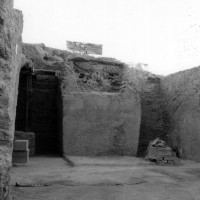

Chapel 37, elevation (drawing by N. Labianca) Chapel 37 (neg 804-2a)

Chapel 37 (neg 804-2a) Chapel 37, detail of the main cultic image (neg 12486-13a)

Chapel 37, detail of the main cultic image (neg 12486-13a) Chapel 37, detail of the main cultic image (neg 11451-2)

Chapel 37, detail of the main cultic image (neg 11451-2) Ground plan of the chapels of the north-east side (Dep. CS 6142)

Ground plan of the chapels of the north-east side (Dep. CS 6142) Chapels 50 and 63 (Dep. CS 6126 6127)

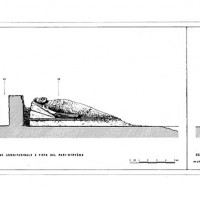

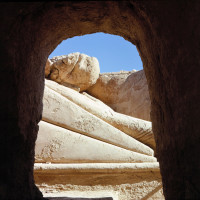

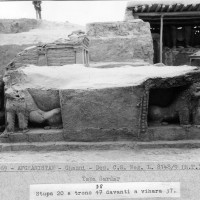

Chapels 50 and 63 (Dep. CS 6126 6127) Chapel 63, the colossal parinirvana seen from the northern entrance (MNAOR 3467)

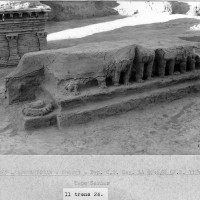

Chapel 63, the colossal parinirvana seen from the northern entrance (MNAOR 3467) Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Stupa 5 (neg 7414-1)

Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Stupa 5 (neg 7414-1) Minor cultic areas - Area 64 , detail of monument 69 representing a miniature fortification wall (neg 9936-9a)

Minor cultic areas - Area 64 , detail of monument 69 representing a miniature fortification wall (neg 9936-9a) Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Stupa 7 ()neg 7402-7

Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Stupa 7 ()neg 7402-7 Stupa 7, detail (neg 7392-1)

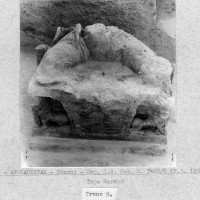

Stupa 7, detail (neg 7392-1) Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Throne 6

Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Throne 6 Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Throne 24

Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Throne 24 Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Throne 9

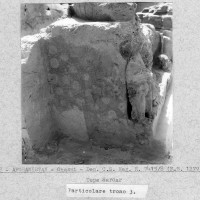

Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Throne 9 Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; here, detail of the moulded decoration of Throne 9 (neg 7418-6)

Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; here, detail of the moulded decoration of Throne 9 (neg 7418-6) Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, detail of the painted decoration of Throne 3

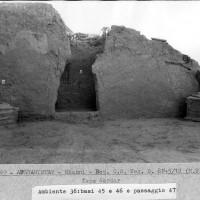

Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, detail of the painted decoration of Throne 3 Minor cultic areas - Room 41 and Stupa 41

Minor cultic areas - Room 41 and Stupa 41 Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Throne 38

Upper Terrace, row of stupas and thrones; in the fore, Throne 38 Minor cultic areas - Room 36

Minor cultic areas - Room 36 Minor cultic areas - Room 75 (neg 12045-9)

Minor cultic areas - Room 75 (neg 12045-9) Minor cultic areas - Area 64 (Dep. CS 4010-e)

Minor cultic areas - Area 64 (Dep. CS 4010-e) Plan and elevation of Chapels 23 and 17 (Dep. CS 4023)

Plan and elevation of Chapels 23 and 17 (Dep. CS 4023)

The early period

The fire of the 7th century CE destroyed the most part of the architectural setting and decoration of the earliest phases of the site. However, the hundreds of sculptural fragments which were found in a filling layer (this in turn composed of layers (5) and (6), “different aspects of the same filling”), as well as the remains of the early architectures, help us to reconstruct the main features of the old sanctuary.

The stylistic and iconographic patterns of the Antique Period 1 (2nd/3rd century - 4th/5th century CE?) are modelled after the “Gandharan” traditions, with a marked Hellenistic flavour. Of the rich original polychromy only traces can now be detected in the fragments of clay sculptures and the scant extant evidence of mural paintings.

Antique Period 2 (5th/6th - 7th century CE?) is characterized by colossal images and the extensive use of gilding, which was also used in “renovating” the sculptures from the earlier period.

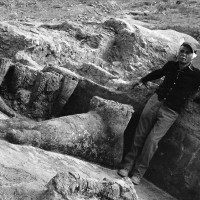

Another picture of the colossal foot from Room 100, highlighting its proportions

Another picture of the colossal foot from Room 100, highlighting its proportions Colossal gilded foot from Room 100 - Antique Period 2

Colossal gilded foot from Room 100 - Antique Period 2 Silenus-like moustached head - TS 1502

Silenus-like moustached head - TS 1502 Head of a young god, presumably the vedic Shakra - TS 1600

Head of a young god, presumably the vedic Shakra - TS 1600 Male head with shaven hair - TS 1403

Male head with shaven hair - TS 1403 Female head with curly head - TS 1063

Female head with curly head - TS 1063 The gold leaf from TS 1870, stuck in the earth deposit

The gold leaf from TS 1870, stuck in the earth deposit Gilded head of a deva from Niche 76, with traces of red, black and brown paint in hair, eyes and eyebrows - TS 1870

Gilded head of a deva from Niche 76, with traces of red, black and brown paint in hair, eyes and eyebrows - TS 1870 Moustached head of a Kushan aristocrat with conical cap - TS 1065 + TS 1515

Moustached head of a Kushan aristocrat with conical cap - TS 1065 + TS 1515 Head of deva from Niche 76, with traces of red paint on the eyebrows and black paint in the hair - TS 1871

Head of deva from Niche 76, with traces of red paint on the eyebrows and black paint in the hair - TS 1871

The recent period

The Recent Period marks an extraordinary revival after the devastation caused by the fire. It is during this period that the chapels were built (or better, re-built) and decorated. The main iconographic subjects, against the wall opposite the entrance, were gigantic Buddha images, accompanied by ancillary deities, and immersed in a rocky landscape which was populated by a variety of human, animal and monstrous figures, as attested by the numerous sculptural fragments found in Layer (4).

The artists took advantage of the physical characteristics of clay to their limits. Clay was used both to convey the colossal solidity of the main images (the Buddha in parinirvāṇa in Chapel 63 measured 15 meters in length), and the lively scenes that surrounded them. The versatile nature of the material was reinforced by the painting and gilding of the surface.

Gilding could either be applied to parts of a sculpture – that was the case of the larger ones – preferring the face and the hands, or to the entire figure, as especially in the case of small figures.

Grotesque being emerging from a rocky landscape in awe at the Buddha, from Chapel 23 - TS 1126

Grotesque being emerging from a rocky landscape in awe at the Buddha, from Chapel 23 - TS 1126 Lokapala (protector of a cardinal point) with helmet, from Stupa 5 - TS 1016

Lokapala (protector of a cardinal point) with helmet, from Stupa 5 - TS 1016 Male gilded figure with long hair, bracelet and necklace, reconstructed from many fragments - TS 1850

Male gilded figure with long hair, bracelet and necklace, reconstructed from many fragments - TS 1850 Standing bodhisattva with paridhana (loincloth) and uttariya (upper garment) still intact, from Chapel 37 - TS 1272

Standing bodhisattva with paridhana (loincloth) and uttariya (upper garment) still intact, from Chapel 37 - TS 1272 Bodhisattva with crossed legs, originally sitting on a lotus, from Chapel 37 - TS 1500

Bodhisattva with crossed legs, originally sitting on a lotus, from Chapel 37 - TS 1500 Head of a bodhisattva with long curly hair, from Chapel 37 - TS 1259

Head of a bodhisattva with long curly hair, from Chapel 37 - TS 1259 Head of a bodhisattva with black hair bound by a double garland, from Vihara 17 - TS 580

Head of a bodhisattva with black hair bound by a double garland, from Vihara 17 - TS 580 Head of bodhisattva from Chapel 37 - TS 1220

Head of bodhisattva from Chapel 37 - TS 1220

Tackling restoration and preservation problems

As customary in Afghanistan and Central Asia, also at Tapa Sardar architectures and sculptures were realised primarily with clay. The plasticity and malleability of this extraordinary material allowed for the production of masterpieces of grace and refinement, whether on a grand or a minute scale. However, clay is also very fragile and loses cohesion and consistency over time. In excavations, it is usually found in shapeless masses or in an extremely precarious state.

For this reason, the Italian Archaeological Mission has always taken the greatest care when digging, restoring and documenting every single discovery: this is the only way to preserve the objects and understand the ideas which gave them life.

First rescue on the site and restoration in the laboratory

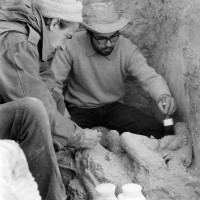

At Tapa Sardar, of particular importance in the fieldwork were the techniques of removal of the artefacts: pre-strengthening and provisional cleanings were completed in the laboratories, where obvious and disturbing fractures were closed and all the pieces were individually consolidated in depth. The interventions followed the criteria of neutrality and reversibility. These operations, carried out systematically in all the excavation campaigns of the Italian Archaeological Mission, allowed a considerable corpus of individual painted or sculpted images to be preserved.

TS 1800 after restoration (MNAOR 3807)

TS 1800 after restoration (MNAOR 3807) Fragments of mural painting TS 1800 during excavation (MNAOR 3497 - CS 4235)

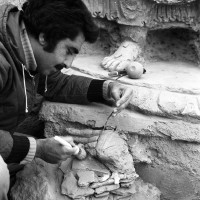

Fragments of mural painting TS 1800 during excavation (MNAOR 3497 - CS 4235) 2003 - Restoration of the Buddha head (TS 1144) at the Kabul Museum

2003 - Restoration of the Buddha head (TS 1144) at the Kabul Museum Head of the Bejewelled Buddha from Chapel 23 (TS 1144)

Head of the Bejewelled Buddha from Chapel 23 (TS 1144) 1970 - Field restoration on a finding from Chapel 37 (R 8993-7)

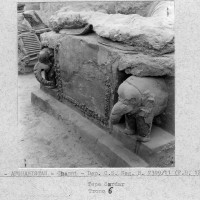

1970 - Field restoration on a finding from Chapel 37 (R 8993-7) 1972 - Restoration of the parinirvana Buddha in Chapel 63 (R 9932-10)

1972 - Restoration of the parinirvana Buddha in Chapel 63 (R 9932-10) 1969 - Strenghtening of base 40 (R 8231-5)

1969 - Strenghtening of base 40 (R 8231-5) 1969 - Workers transporting TS 1144 (R 8225-4)

1969 - Workers transporting TS 1144 (R 8225-4) 1960 - Fragments of a leg of a huge standing Buddha image (L 844-28)

1960 - Fragments of a leg of a huge standing Buddha image (L 844-28) 1970 - Fragment of uttariya (upper garment) from TS 1272 (CS 4175)

1970 - Fragment of uttariya (upper garment) from TS 1272 (CS 4175) Excavation of a bodhisattva head still preserving the original painting

Excavation of a bodhisattva head still preserving the original painting 1970 - Findings on the south-west corner of Chapel 37 (L 807-19a)

1970 - Findings on the south-west corner of Chapel 37 (L 807-19a) Restorer at work in Room 75 (12042-7)

Restorer at work in Room 75 (12042-7) 1969 Room 36, consolidation of sculpture TS 1559 (R 8165-11)

1969 Room 36, consolidation of sculpture TS 1559 (R 8165-11)

Revivifying the past

If restoration saves the physical objects, documentation secures the possibility of reconstructing things no longer extant and transmitting their memory across time. Thanks to the careful archaeological documentation of the 1960s and 1970s is still possible, after decades, to work out reconstructive hypotheses about the original contexts. The description, measurements and finding spot of the fragments are precious hints to their original position and clustering.

A new impulse to the development of reconstructive hypotheses has been given by this project. Graphic reconstructions are now being studied.

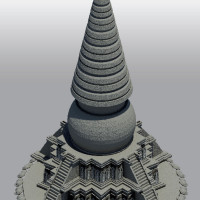

The rows of stūpas and enthroned figures in the Upper Terrace

Among the ongoing studies, there is the hypothetical reconstruction of a series of relatively small monuments. These deserve special attention, as they are the prototypes of architectures and iconographies which developed in Himalayan and Far-Eastern countries. Thus by reconstructing these monuments, we can bridge the gap between apparently distant places and times. At the same time, we can better understand the central role of Afghanistan in the cultural history of Late Antique Asia.

Upper Terrace - The row of stupas and thrones, elevation sketch (Donatella Ebolese)

Upper Terrace - The row of stupas and thrones, elevation sketch (Donatella Ebolese) Upper Terrace - Throne 6, preliminary reconstruction (Anna Maria Fedele)

Upper Terrace - Throne 6, preliminary reconstruction (Anna Maria Fedele) Upper Terrace - Throne 6 (neg 7412-1)

Upper Terrace - Throne 6 (neg 7412-1) Stupa 7 - Preliminary reconstruction (Carlotta Passaro)

Stupa 7 - Preliminary reconstruction (Carlotta Passaro) Stupa 7 (in the fore), Stupa 8 (in the middle) and Throne 6 (neg 7410-7)

Stupa 7 (in the fore), Stupa 8 (in the middle) and Throne 6 (neg 7410-7) Upper Terrace, the row of stupas and thrones during excavation (MNAOR 3411 CS 1799-6)05-Stupa 7 (in the fore), Stupa 8 (in the middle) and Throne 6 (neg 7410-7)

Upper Terrace, the row of stupas and thrones during excavation (MNAOR 3411 CS 1799-6)05-Stupa 7 (in the fore), Stupa 8 (in the middle) and Throne 6 (neg 7410-7) Upper Terrace - The row of stupas and thrones, (Dep. CS 4010 f.3)

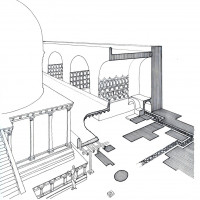

Upper Terrace - The row of stupas and thrones, (Dep. CS 4010 f.3) Isometric view of of the Upper Terrace (Elio Paparatti)

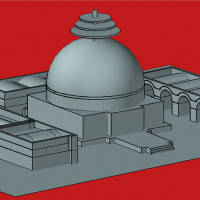

Isometric view of of the Upper Terrace (Elio Paparatti) Upper Terrace, preliminary 3D reconstruction (Danilo Rosati; modified by Donatella Ebolese)

Upper Terrace, preliminary 3D reconstruction (Danilo Rosati; modified by Donatella Ebolese)