By Giulia Forgione

In 2014 it became possible to include in an existing collaboration programme between the Italian Archaeological Mission in Afghanistan and the Afghan National Institute of Archaeology a PhD research project currently underway at the University of Naples ‘L'Orientale’*. The research focused on the vast unbaked clay sculptural production discovered at the Buddhist archaeological site of Tepe Narenj in the Kabul area.

The project was made possible through preliminary agreements with the Afghan National Institute of Archaeology headed by Mr. Abdul Qadir Temori, and in particular with the excavation director at Tepe Narenj, Zafar Paiman.

In the following a brief outline of several aspects of the research will be given with a view to presenting new and certain archaeological evidence obtained in the course of one of the very rare systematic excavations underway in Afghanistan. More importantly it expresses the determination to reopen the debate on the cultural and artistic history of Afghanistan, the interpretation of which is still shrouded in uncertainty. The opportunity was offered precisely by the possibility of comparison with other sites such as Tapa Sardar, which, in addition to its high stratigraphic reliability, covers a time span and cultural phases that partly overlap those of the site of Tepe Narenj.

The site of Tepe Narenj

The site of Tepe Narenj, which literally means “orange hill”, stands on a relief that is currently denoted as Koh-e Zamburak, or “mountain of the small wasp”, situated on the eastern slopes of the Hindukush mountain chain, only a few kilometers South of Kabul; so far only partially investigated, it covers an area of more than four hectares and occupies a dominant position; it faces East and is quite visible from a considerable distance.

Although the site has earlier origins, dated by pottery, palaeographic and numismatic finds to the 2nd-3rd century CE, the period most intensively documented in the excavations, during which the sacred area was reworked, renovated and extended several times, dates to between the end of the 5th century CE and the 9th/10th century CE.

During the earliest phase of this chronological span, which corresponds fully to the Hūṇa era, the site of Tepe Narenj enjoyed a period of great artistic flourishing and a thriving building activity. As suggested by the preserved iconographic programmes this was sustained by powerful and highly motivated local aristocracies.

A second great artistic development is recorded in the late 7th/early 8th century CE, in the Shahi era, during which the renovation and extension of the sanctuary was marked by profound artistic and cultural changes.

General features

The excavations unveiled a complex system of nine sloping terraces (“T”: “Terrasse”, several of which overlying earlier layouts) designed to exploit the slope of the hill and interconnected by a system of steps and smaller terraces (“g”: “gradin”).

On the terraces in the middle portion of the site stood the Main Stūpa (“ST”, T4) and a series of cult chapels (“CH”: “Chapelle”, T5, T6) which still retain traces of large-scale decorative work in polychrome unbaked clay displaying a strong visual impact; these were executed using a (strong) high relief technique completed by pictorial decoration.

At the foot of the hill lies Zone 14, a porticoed area with numerous unbaked clay sculptures in situ although most of it still lies under the modern Muslim cemetery known as Shohada-e Salehin. Other cult chapels have been discovered on the northern (Zone 13, CH 9, 10, 11) and southern slopes (Zone 10, CH 8) of the hill and bear witness to the large size of the sacred area.

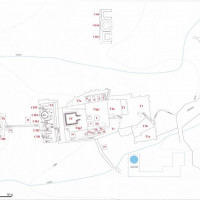

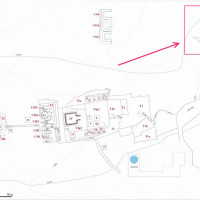

Fig. 5 - Tepe Narenj: general plan of the site

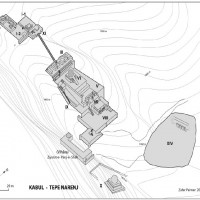

Fig. 5 - Tepe Narenj: general plan of the site Fig. 6 - Axonometric view of the investigated zones

Fig. 6 - Axonometric view of the investigated zones Fig. 7 - The Main Stūpa viewed from the south-west side

Fig. 7 - The Main Stūpa viewed from the south-west side Fig. 8 - The Main Stūpa: east side, detail

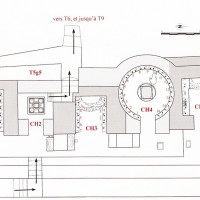

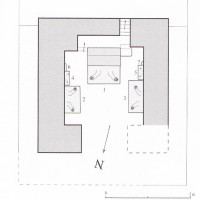

Fig. 8 - The Main Stūpa: east side, detail Fig. 9 - Ground plan of Terrace 5

Fig. 9 - Ground plan of Terrace 5 Fig. 10 - Terrace 5: Chapel 3

Fig. 10 - Terrace 5: Chapel 3 Fig. 11 - Terrace 5: Chapel 4

Fig. 11 - Terrace 5: Chapel 4 Fig. 12 - Chapel 6: main cult image

Fig. 12 - Chapel 6: main cult image Fig. 13 - Zone 14

Fig. 13 - Zone 14 Fig. 14 - Zone 14

Fig. 14 - Zone 14 Fig. 15 - Zone 10: Chapel 8: ground plan

Fig. 15 - Zone 10: Chapel 8: ground plan Fig. 16 - Chapel 8: south-east side

Fig. 16 - Chapel 8: south-east side

The ancient phase

The earliest sculptural phase documented at Tepe Narenj is marked by the exclusive use of unbaked yellow clay, almost always combined with stucco and appropriately represented by both the colossal and smaller sculptures found on the middle section of the site (T5). The aesthetic models are distant from the canons of Hellenistic naturalism (of which only a few automatic and decorative hints remain, for example in the wavy hair styles). The forms are idealized (broad shoulders and narrow waist, sinewy flexible hands, round faces, high eyebrows and bulging eyes). The use of colour is highly symbolic as suggested by the blue colour used for the hair and to emphasize the shape of the eyes.

The terminus post quem of this period is certainly 484 CE as indicated by the finding of a Nezak coin inside the base of the main sculpture in Chapel 3 (the earliest chapel on Terrace 5), representing the Buddha Śākyamuni.

Fig. 17 - Chapel 3: main cult image (Buddha Śākyamuni)

Fig. 17 - Chapel 3: main cult image (Buddha Śākyamuni) Fig. 18 - Chapel 3: south side (worshippers)

Fig. 18 - Chapel 3: south side (worshippers) Fig. 19 - Chapel 3: north side (worshippers)

Fig. 19 - Chapel 3: north side (worshippers) Fig. 20 - Chapel 4: detail (row of Buddhas and bodhisattvas)

Fig. 20 - Chapel 4: detail (row of Buddhas and bodhisattvas) Fig. 21 - Colossal head of a bodhisattva from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 22)

Fig. 21 - Colossal head of a bodhisattva from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 22) Fig. 22 - Seated Buddha from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 17)

Fig. 22 - Seated Buddha from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 17) Fig. 23 - Buddha head with traces of blue paint on the hair from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 28)

Fig. 23 - Buddha head with traces of blue paint on the hair from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 28) Fig. 24 - Buddha head with traces of blue paint on the hair and eyes from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 18)

Fig. 24 - Buddha head with traces of blue paint on the hair and eyes from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 18) Fig. 25 - Buddha head with traces of blue paint on the hair and eyes from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 35)

Fig. 25 - Buddha head with traces of blue paint on the hair and eyes from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 35) Fig. 26 - Head of a king or prince from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 23)

Fig. 26 - Head of a king or prince from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 23) Fig. 27 - Head of a bodhisattva (?) from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 21)

Fig. 27 - Head of a bodhisattva (?) from Chapel 4 (TN CH 4 no. 21)

The recent phase

The most recent sculptural phase is characterized by a typical lengthening and thinning of the figures, by pronounced mannerism and to an even great extent by the use of red unbaked clays, in particular as a surface coating on the sculptures. This phase is fully represented by the sculptures found in Chapel 6, Chapel 8 and in Zone 14, where the chronological links between the two products is suggested by the extensive restoration work carried out in this phase, with red clays being used on sculptures already present in Zone 14 that had originally been executed in yellow unbaked clay.

In view of the fact that Chapels 2 and 4 were built ex novo on Terrace 5 only at the end of the 7th century, the beginning of the recent phase cannot be earlier than the late 7th century (a dating that is in agreement with that commonly accepted for the well-known similar productions, such as the red unbaked clay production of Tapa Sardar and Fondukistan).

Fig. 28 - Chapel 6: detail of the main cult image

Fig. 28 - Chapel 6: detail of the main cult image Fig. 29 - Zone 14: cult image no. 2 (bodhisattva)

Fig. 29 - Zone 14: cult image no. 2 (bodhisattva) Fig. 30 - Zone 14: Buddhas no. 5 (to the left), and no. 4 (showing traces of restauration with red clay)

Fig. 30 - Zone 14: Buddhas no. 5 (to the left), and no. 4 (showing traces of restauration with red clay) Fig. 31 - Zone 14: cult images no. 9 (to the left) and no. 8

Fig. 31 - Zone 14: cult images no. 9 (to the left) and no. 8 Fig. 32 - Zone 14: couple of (princely?) donors (TN Z 14 no. 18)

Fig. 32 - Zone 14: couple of (princely?) donors (TN Z 14 no. 18)

The research

The excellent state of preservation of numerous remains of sculptures found in situ as well as of many fragments discovered in the debris of the collapsed chapels, on the one hand allows an analysis to be made of the plastic production of Tepe Narenj, and, on the other, a comparative study, in the first place with the Tapa Sardar production. Overall the research sets out to shed light on the more significant technical and stylistic aspects of the production for the purpose of making at least a partial reconstruction of the original features of these works and their significance within their specific historical and cultural context. The research will be accompanied by a complete catalogue of the fragments and special care will be taken to define all the material and technical components of each object as well as its iconographic and stylistic features.

As provided for in the work programme of the Italian Archaeological Mission in Afghanistan, chemical analysis is under way of several clay samples from both Tapa Sardar and Tepe Narenj in order to ascertain not only the physico-chemical composition of the materials but also the stylistic and symbolic-religious requirements that led them to be utilized.

The strong tendency towards experimentation (which is evidenced in the use of different techniques and materials and in the introduction of new iconographic elements and new aesthetic canons) attests the great artistic, religious and philosophic vivacity characterizing Afghanistan in the late 5th century. Furthermore, the fact of sharing these elements with other Afghan and non-Afghan sites, above and beyond local regionalisms, is proof of the existence until the 9-10th century CE of an actual specific artistic school sustained by a strong layman’s demand of clear Buddhist origin.

The historical and cultural framework that emerges is extremely important today as, contrary to what is suggested by an outdated and incomplete historiography, it shows that the Hūṇa era was in no way a period of violent invasions and destruction of the Buddhist oecumene and that the history of Buddhism actually extended far beyond the 5th century, as far as the Shahi era and up to the eve of the definitive Islamic conquest.

Preliminary comparison between two important sites

There are numerous historical, artistic and cultural similarities between the site of Tepe Narenj and the site of Tapa Sardar.

The Nezak coin discovered in Chapel 3 can be linked to a well-known typology produced in the Ghazni area, but also current in the Kabul area (Type 217; another slightly later Nezak coin - “type 222” – was found in Zone 14).

The huge size of the figures, the massive presence of lay donors of significance, the importance of polychromy and gilding (the latter attested at Tepe Narenj by probable traces of preparatory layers of bolus), the detailed representation of anatomic features, in addition to the widespread use of unbaked red clay and the tendency to lengthen and thin the figures in later times, are a clear indication of the respect of shared specific aesthetic, iconographic and stylistic conventions (some of the more frequent elements are represented by the incised iris half covered by the upper eyelid, the nasolabial groove represented by a circular furrow, the knee-caps revealed by the draping of the clothes, the feet represented at a later stage in the form today referred to in the West as “Greek foot”).

Commonly shared items are the decorative motifs on crowns, hairstyles and clothing, produced (also using different techniques) as imitations of real objects (see for instance the hoard of gold and jewels discovered at Mes Aynak). These go to make up an accredited repertoire which is used also for the purpose of architectural decoration.

Furthermore, Tepe Narenj has also yielded one of the rare known examples of a type of fire altar in a Buddhist context (on Terrace 9, T 9) discovered so far, with a few variants, only at the site of Tapa Sardar (neg 11461-3) and, less recently, at the site of Tapa Shotor (the case of Mes Aynak remains to be confirmed and no relevant publications are available). It is still not known for what specific ritual or ceremony these altars were used.

The variety and nature of the architectural forms that actually spread in the Buddhist period extend far beyond the bounds of our present knowledge. This is true for the stūpa discovered in Chapel 2 at Tepe Narenj, with its unique form, or the stūpas located in the worship area 41 and 75 in the area South of the upper Terrace of Tapa Sardar (Stūpa 41: Dep. C.S. Neg. 12041/5; Stūpa 75: neg 12045-9), which feature a high degree of creativity in their forms as well as a strong symbolic and religious power which attest the authoritativeness of the sanctuary.

The Tepe Narenj excavations and those of Tapa Sardar thus represent a golden opportunity for archaeology to reconstruct, on a scientific basis, the historical, artistic and cultural developments that took place in the area south of the Hindukush in this period.

Notes

* The Italian Archeological Mission (currently directed by dr. Anna Filigenzi) is co-funded by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the University of Naples 'L'Orientale'. Since 2014 the Mission's activities include the scientific and financial participation in the excavation projects launched by the Afghan National Institute of Archaeology in the site of Tepe Narenj and Qol-e Tut. This partnership is aimed at promoting a unifying approach to the growing mass of archaeological data and, more in general, to the cultural history of pre-Islamic Afghanistan.

Bibliography

Publications on Tepe Narenj and useful references

- AAVV, “Recent Archaeological Works in Afghanistan. Preliminary studies on Mes Aynak excavations and other field works”, Kabul 2013: 41-52.

- Filigenzi Anna, “Forme visive del Buddhismo tardo-antico: una koiné artistica senza nome lungo i percorsi delle Vie della Seta”, in B. Genito e Lucia Caterina (a cura di) Archeologia delle Vie della Seta: Percorsi, Immagini e Cultura materiale, 1o ciclo di conferenze, 14 Marzo-16 Maggio 2012: 38-75. http://ftp.unior.it/cisa/pubblicazioni/viedellaseta/ICiclo/ViedellaSetaI.html#p=38

- Filigenzi Anna, “Post-Gandharan/non- Gandharan: An Archeological Inquiry into a Still Nameless Period” in M. Alram, D.E. Klimburg-Salter, M. Inaba, M. Pfisterer (eds) Coins, Art and Chronology II, The First Millennium C.E. in the Indo-Iranian Borderlands, Wien 2010: 389-406.

- Filigenzi Anna, Roberta Giunta “The Italian Archaeological Mission in Afghanistan”, in B. Cassar and S. Noshadi (eds.) Keeping History Alive: Safeguarding Cultural Heritage in Post-Conflict Afghanistan, Paris-Kabul (UNESCO) 2015: 80-91.

- Filigenzi Anna, Roberta Giunta “Rediscovering the Past, Looking into the Future by the Italian Archaeological Mission in Afghanistan”, in Junhi Han (ed.) From the Past and For the Future: Safeguarding the Cultural Heritage of Afghanistan – Jam and Herat, Paris (UNESCO) 2015: 85-88.

- Paiman Zafar, “Tepe Narenj dar roshnâi do dowr akhir hafriyât (Tepe Narenj à la lumière des deux dernières campagnes de fouilles), Rapport déposé en juin 2012 à l’Institut Afghan d’Archéologie, Caboul 2012, inédit.

- Paiman Zafar, “Histoire sociale, religieuse et militaire de l’empire hephtalite, et bref aperçu sur les Kidarites, les Kaboul Shahis et les Hindu Shahis”, vol. 2, chapitre 25, 2011: 356-369, inédit (en dari).

- Paiman Zafar, “Afghanistan, les Bouddhas colorés des V-VI siècles” in Archéologia n° 473, 2010: 52-65.

- Paiman Zafar, “Monastères bouddhiques à Kaboul”, in Les Nouvelles d’Afghanistan n° 125, 2009: 15-19.

- Paiman Zafar, “Kaboul riche foyer d’art bouddhique”, in Archéologia n° 461, 2008: 56-65.

- Paiman Zafar, “Rapport-e- dūr sevom wa charom hafriyāt-e Tepe Narenj 1385-1386 (Rapport de la troisième et quatrième campagnes de fouille de Tepe Narenj), Institut Afghan d’Archéologie, Caboul 2007, inédit.

- Paiman Zafar, “Région de Kaboul, nouveaux monuments bouddhiques” in Archéologia n° 430, 2006: 24-35.

- Paiman Zafar, “Gozāreš-e ilmī-ye daur-e duvvum-e hafriyāt dar Tepe Nāranj (kenār-e zīyārāt-e Panja Šāh) junūb-e Bālā Ḥisār (tābestān 1384) (Rapport sur la deuxième campagne de fouille de Tepe Narenj, près de la ziyarat de Panja Shah, au sud de Bala Hisar, dans l’été 2005), in Afghanistan Archeological Review, Institute of Archeology, vol. 19-20, Kabul 2006: 114-201.

- Paiman Zafar, “La renaissance de l’archéologie afghane; découvertes à Kaboul” in Archéologia n° 419, 2005: 24-39.

- Paiman Zafar, “Raport-e daura-ye avval-e kāvuš dar sāha-ye Tepe Nāranj (Rapport sur la première campagne de fouille à Tepe Narenj en 2004), in Afghanistan Archeological Review, Institute of Archeology, vol. 17, Kabul 2005: 109-148.

- Paiman Zafar, Alram Michael, “Tepe Narenj à Caboul, ou l’art bouddhique à Caboul au temps des incursions musulmanes” Paris 2013.

- Paiman Zafar, Alram Michael, “Tepe Narenj: A Royal Monastery on the High Ground of Kabul”, in Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archeology 5, 2010: 33-58.

- Taddei Maurizio, “Evidence of a Fire Cult at Tapa Sardar, Ghazni (Afghanistan)” in South Asian Archeology 1981, Cambridge 1984: 263-270.

Taddei Maurizio, Verardi Giovanni, "Tapa Sardar, Second Preliminary Report", in East and West no. 28, 1-4. Rome 1978: 33-135. - Verardi Giovanni, “Homa and Other Fire Rituals in Gandhāra”, Supplemento n° 79 agli Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale, vol. 54 (1994), fasc. 2, Napoli 1994: 1-88.

- Verardi Giovanni, "Osservazioni sulla coroplastica di epoca kusana nel Nord-Ovest e in Afghanistan in relazione al materiale di Tapa Sardar", Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale di Napoli, no. 43, Napoli 1983: 479-504.

- Verardi Giovanni, Parapatti Elio, “From Early to Late Tapa Sardar”, East and West no. 55/1-4, Rome 2005: 405-444.

- Vondrovec Klaus, “Coinage of Nezak”, in M. Alram, D.E. Klimburg-Salter, M. Inaba, M. Pfisterer (eds), Coins, Art, and Chronology II. The First Millennium CE in the Indo-Iranian Borderlands, Wien 2010: 169-190.

List of illustrations

- Fig. 1 - Map data © 2017 Google.

- Fig. 2 - IMG_0155, © Zafar Paiman.

- Fig. 3 - IMG_9230, © Zafar Paiman.

- Fig. 4 - IMG_0196, Paiman 2013: Pl. IX.

- Fig. 5 - Paiman 2013: Pl. VI.

- Fig. 6 - Paiman 2011, unpublished (cf. Paiman 2010: fig. 2).

- Fig. 7 - TN_2006, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XIII).

- Fig. 8 - IMG_9174, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XIII).

- Fig. 9 - Paiman 2013: Pl. XVa.

- Fig. 10 - IMG_4215, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XVI).

- Fig. 11 - IMG_9081, Paiman 2013: Pl. XVII d.

- Fig. 12 - IMG_1647, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XIXa).

- Fig. 13 - Paiman 2013: Pl. VI.

- Fig. 14 - IMG_0743, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXII).

- Fig. 15 - Paiman 2013: Pl. XVIII b.

- Fig. 16 - IMG_3332, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XVIII).

- Fig. 17 - IMG_4217, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XVI a).

- Fig. 18 - IMG_1892, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XVI b).

- Fig. 19 - IMG_1420, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XVI c).

- Fig. 20 - IMG_011, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XVII b).

- Fig. 21 - Tepe Narinj (72), © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXVI no. 22).

- Fig. 22 - Bouddha assis_ch 4, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXV no. 17).

- Fig. 23 - Tepe Narinj (89), © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXVI no. 28).

- Fig. 24 - Tepe Narinj (82), © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXV no. 18).

- Fig. 25 - Tepe Narinj (37), © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXVII no. 35).

- Fig. 26 - Tepe Narinj (86), © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXVI no. 23).

- Fig. 27 - Tepe Narinj (28), © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXVI no. 21).

- Fig. 28 - IMG_9726, © Zafar Paiman.

- Fig. 29 - IMG_3666, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXIII a).

- Fig. 30 - IMG_0639, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXIII a).

- Fig. 31 - S 9, 8 (2), © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXIII a-b).

- Fig. 32 - IMG_5051, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: frontispiece).

- Fig. 33 - IMG_5163, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXI).

- Fig. 34 - IMG_5303, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XXI).

- Fig. 35 - Tepe Narenj 012, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XV).

- Fig. 36 - IMG_1082, © Zafar Paiman (cf. Paiman 2013: Pl. XV).

- Fig. 37 - IMG_1848, Paiman 2013: Pl. XIX b.